It was in 2015, at the onset of July, when millions of people worldwide enthusiastically supported homosexual marriage by using the rainbow filter on Facebook (Wecker, 2015). At the time, I was in the ninth grade and had studied in eight schools across eight districts of the country, which had allowed me to curate many acquaintances, mostly my age, on my Facebook.

However, in my then-Facebook world, only one person joined the gang and actively displayed their support. I also wanted to jump on the bandwagon, but I couldn't. Quickly enough, I had good enough reasons to suppress my urge to show solidarity. The only supporter in my network received hate comments, encountered bullying, and received unsolicited messages from strangers for supporting the cause.

Eventually, they had to take the picture down and deactivate their profile for a few days. Unfortunately, I couldn't afford to do the same due to my unbearable personal history of being bullied for being unmasculine. Showing support for a cause like this would only add fuel to the flame in which I was seemingly inescapably trapped.

Gradual progress?

Many things have changed since 2015: The world, the country, my surroundings, a lot of things, indeed. From fearing the filter or even liking a pro-LGBTQ post to reaching a point where witnessing such pieces of content became routine, the journey has been great. Alternatively, that is how it looks on the surface.

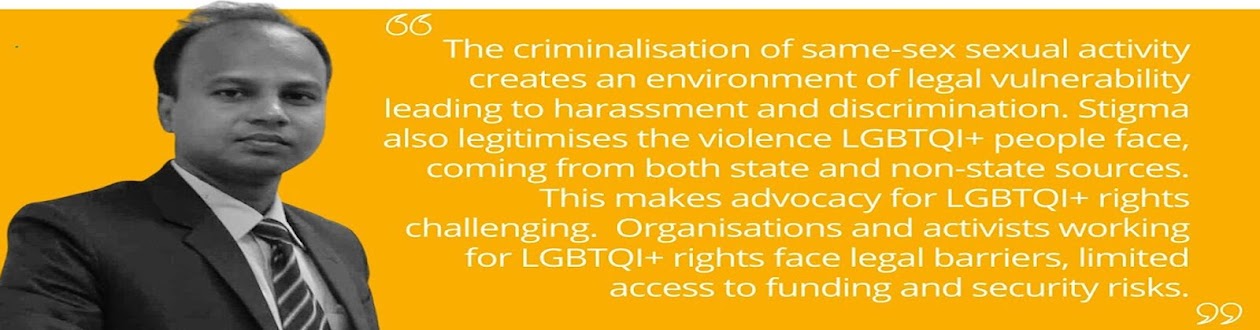

Within Bangladesh's cis/hetero-normative landscape, identifying with an alternative gender identity and/or sexual orientation has never been easy. Being a vocal ally can result in deleterious repercussions too. Considering the prevalent homophobia, transphobia, and hateful remarks the LGBTQ community regularly encounters, remaining in the closet seems like the only safe option. The country is still unprepared to understand the concept of gender identity and accept any gender that does not fall under the binary system, minus some level of tolerance the Hijra community is blessed with.

Unlike Hijras, other sexual and gender minorities cannot express their identities openly (Macdonald, 2021). Between the end of the Raj in 1947 and East Pakistan's independence from Pakistan in 1971, queer rights were not the focal points of any of the groups. Linguistic and cultural autonomy were the two quintessential Bengali nationalist struggles.

Consequently, as Ahmed (2019) puts it, no protest or liberation movement specifically for the queer population has happened. Fast forward to 2013, hijras were granted to be considered the “third gender” by the government. The conversation remains incomplete without mentioning the story of Xulhaz Mannan, the founder of the first LGBTQIA-themed Bangladeshi magazine Roopban. Queer activists, Mahbub Rabbi Tonoy and Xulhaz Mannan, were killed in 2016 by Islamist extremists due to their LGBTQ rights activism.

Seeing the Bangladeshi government hold the activists responsible for their deaths, mentioning that their advocacy for unnatural sex is a criminal offense and is against Bangladeshi culture, many LGBTQ activists went discreet. Many projects and activities took down their social media pages. A number of activists applied for asylum in the US, Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands.

A heavily regulated arena

Social media in Bangladesh is one of the heavily regulated and supervised spheres. After 2016, activists and community members have become increasingly critical of the politics of visibility and the harmful impacts it may have on one's life in Bangladesh's current political landscape.

Despite all that, somehow, social media platforms are now becoming heavier with queer-friendly content in Dhaka. This is clearly more noticeable as people are using social media spaces to show support for the LGBTQ rights through virtual content. The West-centric ideas of queer liberation and LGBTQ rights are becoming more common among people of this country, in which the localization of social media has played a huge role.

Conducted among urban affluent middle-class youths with access to mainstream English education, aged between 18 to 24, my ethnography reveals that the people vocal about queer rights online belong to an affluent social class with access to English education and the language.

They feel more at ease being expressive online than offline. They are aware of the uncertainties surrounding whether or not a discourse related to LGBTQ rights would be efficient in the virtual sphere. They use English, customizable privacy settings on social media platforms, and lie if needed to narrow down the chances of receiving backlash. As an afterthought, the reasons why people are suddenly becoming so outspoken about LGBTQ rights in an unsafe country like Bangladesh are nuanced. Quite understandably so.

A cultural thing?

The reason can be rooted in generational change or cultural agency. Concepts like these are so intertwined that the compartmentalization of those is inconceivable. Given the laws and stigma, it is worth exploring how the vocal supporters imagine their fallback. The overall queerization of Bangladeshi social media spaces might not highlight every kind of nuance, especially those that can be hidden due to the lack of class intersectionality and the hegemonic power of Western labels.

As argued by Chaney, Sabur, and Sahu, despite the shortcomings of civil society organizations, their report submissions to UPR are, in some way, contributing to the overall advancement of LGBTQ rights.

There are projects like "Dhee" and organizations like "Mondro" that are working for the progress of the discourses surrounding queer rights. Admittedly, visible works are being done. Then again, “LGBTQ rights” has not yet become a buzzword within the socio-political realm. Then, what are the stories behind the interlocutors' becoming supporters of this cause?

But how supportive are their family members of their stance on this issue? It is worth considering that being an ally of the LGBTQ community is also stigmatized, which leads us to question whether active allies are likely to become a new minority. If the visibility of LGBTQ-themed content online continues to increase, what would be the broader consequences within the national scenario, assuming section 377 would not be abolished anytime soon?

Indeed, these are important points to consider. It's best to be critical of the discourses surrounding progress, as a narrow view of it may prevent us from seeing whether it is accommodating everyone in the perceived journey of moving forward.

No comments:

Post a Comment